Wild stingless bees provide the inhabitants of Baritú in Salta with pollen, wax, and propolis. Researchers study the uses and characteristics of these products for their conservation and value.

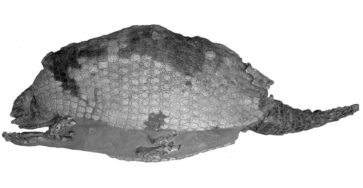

Before the introduction of the “European bee” (Apis mellifera), different melipona species – a group of native stingless bees-, were the main suppliers of honey for the native inhabitants of the American continent. Some communities that live in the yungas of Salta, maintain the habit of collecting the hives of these native bees and use their honey, pollen, wax, and propolis for medicinal and food purposes.

Studies performed by CONICET researchers described picking methods and how the inhabitants of Baritú use local melipona bees. The scientists had also conducted a botanical characterization of the honey, which helped to find that the bees feed mainly on native species flowers, providing the products with unique characteristics.

“The studies revealed that mostly all inhabitants use the products of the same local meliponas’ hives in a similar way. The honey and the pollen are used as food and ingredients of beverages and medicinal preparations, the wax is used for the production of candles, and the propolis as fuel element in ritual contexts”, Norma Hilgert, CONICET independent researcher at the Instituto de Biología Subtropical of Misiones (IBS, CONICET–UNaM) [Subtropical Biology Institute of Misiones].

The objective of these scientific studies, which were jointly developed with the Centro de Investigaciones y Transferencias de Jujuy (CIT, CONICET-UNJU) [Research and Transference Centre of Jujuy] is to value and make good use of the potential these resources for the community. This is a new outlook that combines the approach of cognitive anthropology, which focuses on the interface between biology and anthropology, with palynology, a discipline that is part of botany and is devoted to the study of pollen.

The survey of the relationship between the melliferous insects and the inhabitants of Baritú in Salta began in 2011 and was developed by the team composed of Norma Hilgert, a researcher at the IBS of Puerto Iguazú; Liliana Concepción Lupo, associate researcher at the CIT Jujuy and Fabio Fernando Flores, doctoral fellow at the CIT Jujuy.

One of the studies was specifically oriented to the botanic and geographical characterization of the honey of “mansita” (Plebeia intermedia), one of the more most well known and locally valued melipona bee species. Qualitative tests revealed that this species uses mainly native trees as a food source. “This is a very significant factor because the product comes from native flora and bees, what generates unique honey with a more interesting potential at a commercial level”, Lupo comments.

The inhabitants of the yungas who participate in this study work in family agriculture and transhumance livestock. Their family economy is of subsistence farming and most of the products obtained from the melipona bees are used for consumption. Nevertheless, in some families, the honey is particularly important because they are used as one product for bartering with other communities.

Hilgert comments that there is a project at the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación [Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development] in which there will be new incorporation in the Código Alimentario Nacional [National Food Code]. It is about the Tetragonisca fiebrigi (jatei), a new species of melipona present in the north of Argentina, what will provide the possibility of developing the commercialization of the product as a practically exclusive resource of these communities. “Our studies show that there are other lesser-known honeybees that are vital for some communities and have a great potential to be developed in the future”, the scientist states.

In order to turn the honey into a new source of income for the inhabitants, there have been other initiatives. “Together with a beekeeper producer from Santa Fe, we conducted a pilot in which we raised “mansita” bees with the help of two local families. We practiced the transfer from the hive in the tree to a breeding box and identified how to take after this species in particular”, Fabio Flores comments. “We plan to track the progress and health of the hives in each of the visits to Baritú”, he adds.

The studies performed by the team of scientists from Misiones and Jujuy provided, from an ethnobiological and palynological perspective, the first contributions regarding the wild honey of the Andean populations and the food sources selected by the melipona bees. Through the development of this theme, the researchers aim to create tools for the production of these resources, promoting not only the conservation of the natural environments of these insects but also the economy of their inhabitants.

Before the introduction of the “European bee” (Apis mellifera), different melipona species – a group of native stingless bees-, were the main suppliers of honey for the native inhabitants of the American continent. Some communities that live in the yungas of Salta, maintain the habit of collecting the hives of these native bees and use their honey, pollen, wax and propolis for medicinal and food purposes.

Studies performed by CONICET researchers described picking methods and how the inhabitants of Baritú use local melipona bees. The scientists had also conducted a botanical characterization of the honeys, what helped to find that the bees feed mainly on native species flowers, providing the products with unique characteristics.

“The studies revealed that mostly all inhabitants use the products of the same local meliponas’ hives in a similar way. The honey and the pollen are used as food and ingredients of beverages and medicinal preparations, the wax is used for the production of candles, and the propolis as fuel element in ritual contexts”, Norma Hilgert, CONICET independent researcher at the Instituto de Biología Subtropical of Misiones (IBS, CONICET–UNaM) [Subtropical Biology Institute of Misiones].

The goal of these scientific studies, which were jointly developed with the Centro de Investigaciones y Transferencias de Jujuy (CIT, CONICET-UNJU) [Research and Transference Centre of Jujuy] is to value and make good use of the potential these resources for the community. This is a new outlook that combines the approach of cognitive anthropology, which focuses on the interface between biology and anthropology, with palynology, a discipline that is part of botany and is devoted to the study of pollen.

The survey of the relationship between the melliferous insects and the inhabitants of Baritú in Salta began in 2011 and was developed by the team composed of Norma Hilgert, researcher at the IBS of Puerto Iguazú; Liliana Concepción Lupo, associate researcher at the CIT Jujuy and Fabio Fernando Flores, doctoral fellow at the CIT Jujuy.

One of the studies was specifically oriented to the botanic and geographical characterization of the honeys of “mansita” (Plebeia intermedia), one of the more most well known and locally valued melipona bee species. Qualitative tests revealed that this species uses mainly native trees as food source. “This is a very significant factor because the product comes from native flora and bees, what generates a unique honey with a more interesting potential at a commercial level”, Lupo comments.

The inhabitans of the yungas who participate in this study work in family agriculture and transhumance livestock. Their family economy is of subsistence farming and most of the products obtained from the melipona bees are used for consumption. Nevertheless, in some families, the honeys are particularly important because they are used as one product for bartering with other communities.

Hilgert comments that there is a project at the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación [Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development] in which there will be a new incorporation in the Código Alimentario Nacional [National Food Code]. It is about the Tetragonisca fiebrigi (jatei), a new species of melipona present in the north of Argentina, what will provide the possibility of developing the commercialization of the product as a practically exclusive resource of these communities. “Our studies show that there are other lesser-known honeybees that are vital for some communities and have a great potential to be developed in the future”, the scientist states.

In order to turn the honeys into a new source of income for the inhabitants, there have been other initiatives. “Together with a beekeeper producer from Santa Fe, we conducted a pilot in which we raised “mansita” bees with the help of two local families. We practised the transfer from the hive in the tree to a breeding box and indentified how to take after this species in particular”, Fabio Flores comments. “We plan to track the progress and health of the hives in each of the visits to Baritú”, he adds.

The studies performed by the team composed of scientists from Misiones and Jujuy provided, from an ethnobiological and palynological perpective, the first contributions regarding the wild honeys of the Andean populations and the food sources selected by the melipona bees. Through the development of this theme, the researchers aim to create tools for the production of these resources, promoting not only the conservation of the natural environments of these insects, but also the economy of their inhabitants.

*This piece was originally published on CONICET. It can be found in its entirety here